Reviving a Nation Through Words and Wisdom

The Language That Shaped a Vision

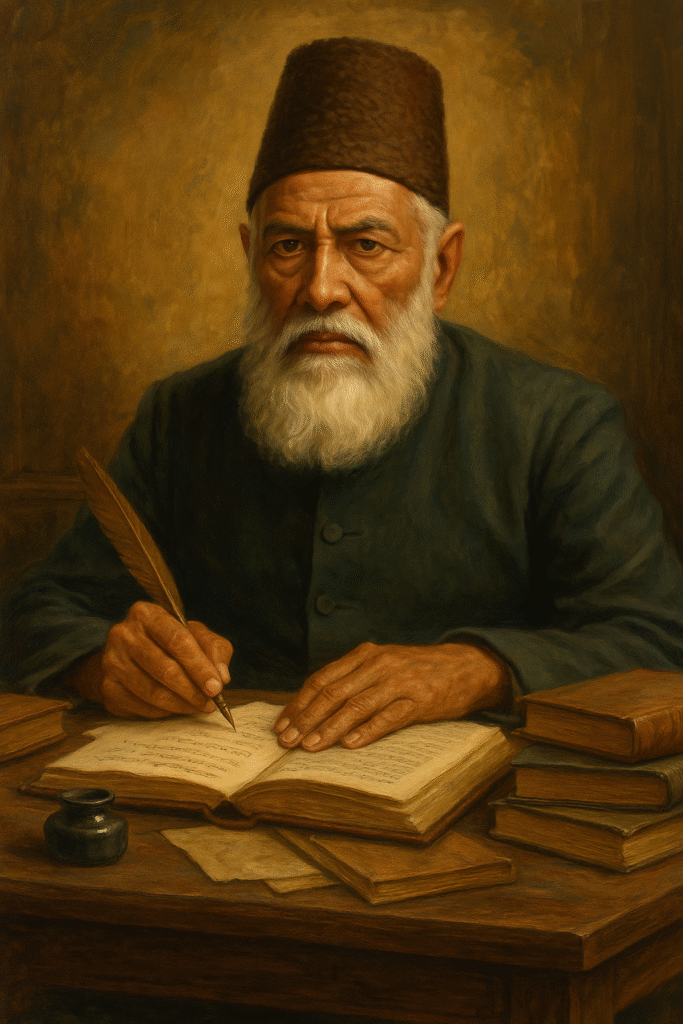

Sir Syed Ahmad Khan emerged in the heart of 19th-century India as a beacon of hope when despair and confusion clouded the Muslim mind after the collapse of the Mughal Empire and the tragic revolt of 1857. At a time when many had surrendered to hopelessness, Sir Syed stood resolute with faith in reason, education, and the written word. A reformer, philosopher, educationist, and pioneer of intellectual awakening, he was not merely a thinker — he was a movement unto himself. His pen became his weapon, enlightenment his mission, and Urdu the language of his revolution — a language through which he sought to revive intellect, identity, and the spirit of a fallen community.

At that time, the Muslim community of India stood torn between the grandeur of a lost past and the uncertainty of a Westernized future. The echo of Delhi’s fallen culture lingered in broken hearts. Yet Sir Syed refused to see ruin—he saw possibility. He realized that revival would not come through swords, slogans, or nostalgia but through books, schools, and scientific curiosity. In his mind, Urdu was not only a language of poets but a medium of empowerment, capable of guiding a lost community toward progress.

To Sir Syed, Urdu was more than a linguistic expression; it was the soul of Indian Muslim identity—a language that carried within it centuries of shared history, culture, and faith. He believed that Urdu could unite minds divided by class and region, and serve as a bridge between the East and the West, between the ancient and the modern. Through it, he sought to transform thought, refine ethics, and reform society.

Thus began one of the greatest intellectual movements of modern South Asia—the Aligarh Movement—a revolution of minds that changed the course of Muslim education and redefined the destiny of Urdu. It was through this vision that Sir Syed proved a profound truth: that a language, when nurtured with knowledge and conviction, can become a force of civilization. Urdu, under his pen, became a language of light—uniting the heart’s emotion with the mind’s reason, and giving a voice to a community on the path to rebirth.

Early Life and Awakening: Seeds of a Reformer

Born on October 17, 1817, in Delhi, Sir Syed Ahmad Khan grew up in a family deeply rooted in learning and literature. The fragrance of Urdu poetry, calligraphy, and Persian prose surrounded his early years. His family’s closeness to the Mughal court had exposed him to the grandeur of Indo-Islamic culture and the linguistic richness of Urdu.

As a young man, Sir Syed joined the British administration as a civil servant. His job in the colonial system gave him first-hand exposure to Western systems of education and governance. Yet, he also witnessed the growing alienation and poverty among Muslims who remained distant from modern learning. This realization would later ignite his reformist spirit.

The Revolt of 1857 proved to be a turning point in his life. The devastation that followed and the misunderstanding between the British and the Muslim community convinced him that the survival of Muslims in India depended on education and intellectual progress. He believed that Urdu, being the language of the common people and the elite alike, could serve as a powerful medium for spreading modern knowledge among Indian Muslims.

The Vision — Education and Urdu as Instruments of Revival

Sir Syed’s brilliance rested in his remarkable understanding of how education, identity, and language intertwine to shape the destiny of a community. He was far ahead of his time in recognizing that a people deprived of their language are deprived of their soul. In his view, education was not just a means to employment or social advancement—it was a moral and cultural awakening. But such awakening, he insisted, could never be achieved if Muslims became strangers to their own linguistic and intellectual heritage.

He saw that Urdu, deeply rooted in India’s soil and in Muslim civilization, could become a bridge between faith and modernity. It was not a relic of the Mughal court or a symbol of feudal refinement—it was a living, breathing language of the people, capable of expressing science, reason, and progress. In Sir Syed’s hands, Urdu transformed from a poetic language into a language of thought, reform, and knowledge.

Through his journals, essays, and educational institutions, he tirelessly emphasized the importance of acquiring modern scientific knowledge, particularly through English, while simultaneously preserving Urdu as the cultural and emotional anchor of the Muslim identity. For Sir Syed, English was the window to the world, but Urdu was the mirror of the self. He urged his community to learn both—so that they might face the modern world without losing their roots.

In his speeches, Sir Syed repeatedly reminded his followers that the power of a nation lies not merely in its wealth or arms but in its intellectual and linguistic strength. A community that forgets its language, he warned, forgets its history, its character, and its moral compass. Thus, his mission became twofold: to uplift Muslims through modern education and to safeguard their linguistic and cultural identity through Urdu.

The harmony between these two objectives became the hallmark of the Aligarh Movement. In the classrooms of the Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College, in the pages of the Tehzib-ul-Akhlaq, and in the translations of the Scientific Society, Sir Syed’s vision came alive—uniting science and spirituality, reason and faith, East and West.

He believed that Urdu had the rare capacity to translate the language of modern science into the idiom of the heart. It could carry Newton’s discoveries and Shakespeare’s ideas alongside Ghalib’s poetry and Rumi’s philosophy. In that synthesis lay his dream: a generation educated in Western knowledge yet rooted in Eastern values, fluent in English yet emotionally bound to Urdu—a generation that could rebuild its future with both intellect and soul.

Sir Syed’s vision thus transcended mere reform. It was an act of cultural preservation through progress—a revival of faith in learning, expression, and the unique identity of Indian Muslims. Through education and Urdu, he sought not only to enlighten minds but to revive the very spirit of a nation.

The Scientific Society and the Power of Translation

In 1863, Sir Syed Ahmad Khan established the Scientific Society in Ghazipur, later relocating it to Aligarh, driven by a visionary purpose—to translate Western scientific and literary works into Urdu. At a time when the English language was a privilege of the elite and the Muslim community lagged far behind in modern education, Sir Syed saw translation as a revolutionary tool for social transformation. His goal was to make the treasures of global knowledge available to the common people in their own language, empowering minds that had been left behind by colonial modernity.

The Scientific Society became a cornerstone of intellectual awakening in India. It was not simply a publishing body; it was a movement of minds. Under Sir Syed’s leadership, scholars and translators worked passionately to bring English texts on science, technology, economics, history, and philosophy into Urdu. Each translated work was more than a linguistic exercise—it was a bridge between civilizations, a dialogue between the East and the West.

Through this initiative, Sir Syed expanded the functional horizon of Urdu. Until then, Urdu was celebrated primarily for its literary beauty and poetic expression. But Sir Syed envisioned something greater: he transformed Urdu into a language of intellect, analysis, and inquiry. Under his vision, Urdu became capable of discussing Newton’s laws, Darwin’s theories, and the ethics of modern governance with the same grace it once used for ghazals and qasidas.

In 1866, he launched the Aligarh Institute Gazette, the official organ of the Scientific Society. This publication marked a turning point in Urdu journalism and modern education. The Gazette was published bilingually—in Urdu and English—ensuring that the educated elite and the general Muslim populace could both access the same body of thought. It contained essays on scientific inventions, political reforms, education, and moral philosophy. It reported on global discoveries and local challenges, gradually shaping a new generation of readers who could think critically and globally.

Sir Syed firmly believed that the key to national progress was intellectual accessibility—and for Muslims, that accessibility depended on Urdu. He once remarked that if scientific ideas could be read and understood in Urdu, then education would no longer remain the privilege of a few but become the right of all. This conviction turned his Scientific Society into the foundation of a new kind of Urdu modernism, one that united faith with reason and tradition with innovation.

The Society’s meetings often became centers of dialogue and debate, where scholars and students discussed scientific and philosophical questions in Urdu. It was here that a new culture of inquiry took root—a culture that valued both modern learning and linguistic pride. In a society recovering from the trauma of 1857, this effort rekindled hope and curiosity.

The Aligarh Institute Gazette thus became far more than a publication—it was a revolution printed in ink. Every issue represented Sir Syed’s dream of an educated, progressive Muslim community. The Gazette reached cities and small towns alike, carrying the message that Urdu could be the language of both heart and intellect, poetry and precision, emotion and evidence.

By blending scientific translation with moral commentary, Sir Syed made Urdu the language of modern thought. His Scientific Society laid the foundation for future generations of writers, journalists, and educators who would continue to use Urdu as a means of awakening minds. It was through this movement that Sir Syed proved the transformative power of translation—not only as a linguistic act but as a tool of civilizational renewal.

In essence, the Scientific Society was more than an institution—it was a declaration. It announced to the world that Urdu was not a fading echo of the past, but a vibrant voice of progress, capable of carrying the knowledge of an evolving world. Through it, Sir Syed Ahmad Khan gave Urdu a new identity: the language of reason, reform, and renaissance.

Tehzib-ul-Akhlaq: Reforming Minds Through Urdu Prose

In 1870, Sir Syed launched another historic Urdu journal — Tehzib-ul-Akhlaq (The Social Reformer). This publication was a mirror to his heart and intellect. Through its pages, he communicated moral, social, and intellectual reform directly to the people in their own language.

“Tehzib-ul-Akhlaq” carried essays on ethics, religion, women’s education, superstitions, and the need for rational thinking. It encouraged Muslims to open their minds to progress while staying rooted in faith and culture. The magazine’s elegant Urdu prose was revolutionary for its time — simple, direct, and persuasive. It proved that Urdu could express not only poetic beauty but also rational discourse and intellectual clarity.

By making Urdu the vehicle for modern reform, Sir Syed gave the language a new dignity. It was no longer just the tongue of poets and courtiers — it became the language of reason, reform, and renaissance.

Founding of the MAO College: Education as the Language of Empowerment

Sir Syed’s ultimate dream materialized in 1875, when he founded the Madarsatul Uloom, later known as the Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental (MAO) College, in Aligarh. This institution became the nucleus of the Aligarh Movement and the fountainhead of modern Muslim education in India.

Modeled after Oxford and Cambridge, the MAO College represented a perfect synthesis of Eastern culture and Western learning. The college’s medium of communication, administration, and thought retained a deep respect for Urdu. Sir Syed ensured that Urdu remained the connecting language between students and teachers, between intellect and emotion.

He believed that language was not just a tool of communication but an instrument of identity. By nurturing a new generation fluent in both English and Urdu, he built the foundation for a community that could engage with the modern world without losing its roots.

The Defense of Urdu: A Symbol of Cultural Identity

Sir Syed’s defense of Urdu took on a political dimension during the Hindi-Urdu controversy of the late 19th century. When certain groups demanded that Hindi replace Urdu in official domains, Sir Syed passionately argued for Urdu’s continued use as a symbol of cultural unity and intellectual continuity.

He believed that Urdu had evolved as a bridge language between diverse communities — Hindus and Muslims alike — and was the shared heritage of India. To him, Urdu was not a sectarian language; it was the voice of Indian civilization itself.

He warned that replacing Urdu with Hindi would divide the hearts of the people and weaken the cultural fabric of India. His eloquent defense of Urdu in speeches and writings inspired generations of Urdu scholars and journalists to carry forward his mission.

Sir Syed and Urdu Journalism: A Pen that Awakened a Nation

The power of Sir Syed’s pen reshaped the destiny of Urdu journalism. Through his journals — the Aligarh Institute Gazette and Tehzib-ul-Akhlaq — he demonstrated that the Urdu press could be both informative and reformative.

His style of writing was simple yet profound, persuasive yet polite. He avoided emotional rhetoric and instead appealed to logic and common sense. Under his influence, Urdu journalism became a tool for spreading education, civic sense, and reform.

Many of his contemporaries and followers, inspired by his example, went on to establish their own Urdu newspapers and magazines. Thus, the seeds of modern Urdu journalism were sown in the fertile soil of Sir Syed’s intellect.

The Aligarh Movement: Language as the Heart of Renaissance

The Aligarh Movement, inspired by Sir Syed’s vision, was not merely an educational effort; it was a cultural and linguistic renaissance. It aimed to reshape the thinking of Indian Muslims and to make Urdu the unifying force of this revival.

From schools to societies, from debates to publications, Urdu became the language of intellectual and emotional awakening. It served as the medium through which modern sciences, philosophy, and ethics reached the masses. The Aligarh Movement thus turned Urdu from a symbol of nostalgia into a language of progress — a tool of empowerment and enlightenment.

Through this movement, Sir Syed demonstrated that language and education are two sides of the same coin. Without Urdu, Muslims would lose their identity; without education, they would lose their future.

Philosophy of Language: Urdu as the Mirror of Civilization

Sir Syed viewed Urdu as more than words — it was an embodiment of history, values, and aesthetics. He once wrote that a nation that loses its language loses its soul. For him, Urdu represented the composite culture of India, blending Persian elegance with Hindi warmth, and carrying the fragrance of centuries of coexistence.

His writings gave Urdu prose a new purpose — clarity of thought, reformist zeal, and moral refinement. He transformed Urdu from a literary medium into a social force, capable of shaping thought and public opinion.

Even in his educational institutions, he encouraged Urdu debates, poetry recitations, and essay writing to ensure that students developed both intellect and eloquence. He believed that an educated man must also be a man of expression — and Urdu was the key to that expression.

Legacy: Sir Syed’s Enduring Gift to Urdu and India

Sir Syed Ahmad Khan passed away on March 27, 1898, but his ideas outlived him. His tomb beside the grand mosque of Aligarh Muslim University remains a symbol of faith in education and progress.

The institutions and movements he inspired — from the MAO College to the All India Muslim Educational Conference — carried forward his mission. Urdu newspapers, magazines, and literary societies that emerged after his time owed their spirit to him.

Even today, every Urdu speaker who values logic, enlightenment, and self-reform owes a debt to Sir Syed. His efforts preserved Urdu as a language of intellect when it could have faded into mere nostalgia. He gave it new life — as a language that breathes knowledge, reform, and resilience.

Conclusion: Sir Syed’s Dream Lives On

Sir Syed Ahmad Khan’s contribution to the promotion of the Urdu language is not merely historical — it is timeless. He transformed Urdu from the courtly speech of poets into a living, dynamic force of education and social change. Through his pen, Urdu became the voice of a community that refused to surrender to ignorance or inferiority.

He reminded his people that progress begins with words — written, read, and understood. His life teaches us that a nation can only rise when its language rises with it. The light that he kindled through the Aligarh Movement continues to shine wherever Urdu is read, spoken, or loved.

Urdu lives today because Sir Syed Ahmad Khan believed in its power — the power to unite hearts, uplift minds, and inspire generations toward knowledge and dignity.